La bohème

Details

In Brief

Some operas are legendary. None more so than Puccini's work telling the tale of young bohemians in Paris, in which one of the most beautiful romances in operatic literature begins with a burnt-out candle and a misplaced key.There are also legendary opera productions, such as this one directed by Kálmán Nádasdy. With Gusztáv Oláh's marvellous scenery, it is a genuine example of theatrical history that has remained on the Hungarian State Opera repertoire since 1937, with nearly 1000 performances to date. Some things are timeless. This wonderful production is unquestionably one of them.

Parental guidance

Events

Premiere: May 11, 1937

Synopsis

Act I

Rodolfo and Marcello are freezing in their cold attic-room. Despite the poet throwing the manuscript of his play in the fire, the burning love scenes cannot exude enough heat. Colline arrives - with empty hands, as pawnshops are closed on Christmas Eve. Schaunard, however, brings money and delicious food. They divide the money, and eat ravenously. Unexpectedly, the landlord turns up to collect the unsettled rent, but soon they manage to get rid of him, and make their way to the café. However. Rodolfo has to write a poem first, so he follows his three friends later. Hardly has he got down to work when there is a knock at the door: Mimì is standing at the threshold. The wind has blown her candle out. The two hearts soon reconcile, and love starts to blossom in the small attic-room lit by the magical moonlight.

Act II

While a colourful crowd is whirling in the bustling streets, in Cafe Momus the four good friends and Mimì are celebrating Christmas Eve. Marcello's former love, Musetta appears with an elderly gallant, Alcindoro. She immediately seizes the opportunity to regain the painter's affection. With some clever acting, she loses the fooled gallant, and falls into Marcello's arms. As the bohemians have run out of money, when Alcindoro returns to the cafe he finds only the unsettled bill.

Act III

At a foggy and cold dawn near Barriére d'Enfer, in the outskirts of Paris. Mimì is looking for Marcello, who is living with Musetta in the tavern next door. She tells him of her grief: Rodolfo is continuously torturing her with his jealousy, and always suggests that they should separate. Both suffer terribly, and still cannot live without the other. Marcello promises to help them. Mimì walks off, but after some steps she hides behind a tree. Rodolfo steps out of the tavern, and after some hesitation he tells his friend the reason for his strange behaviour. He still passionately loves Mimi, as strongly as at the start, but the girl is fatally ill; she only has a chance to survive if they separate and Mimì finds someone who can provide more adequate living conditions. Mimì's loud weeping reveals her presence and that she has heard everything. Mimì and Rodolfo, both in tears, decide to remain together until the spring, while Musetta and Marcello start one of their usual quarrels.

Act IV

Rodolfo and Marcello are working in the attic-room again, or, rather, they would be working if their memories did not disrupt their imagination. They are both daydreaming about Mimì and Musetta. Schaunard arrives with Colline, and the mood brightens. When the high spirits are at their zenith, Musetta arrives suddenly: Mimì is coming. She has collected all her strength so she could die in the place where she used to be so happy. The two lovers are left alone, and they recall their first encounter. Then the bohemians and Musetta return one by one. When Colline, the last to arrive, closes the door, Mimì – silently, and almost unnoticeably – falls into an eternal sleep.

Media

Reviews

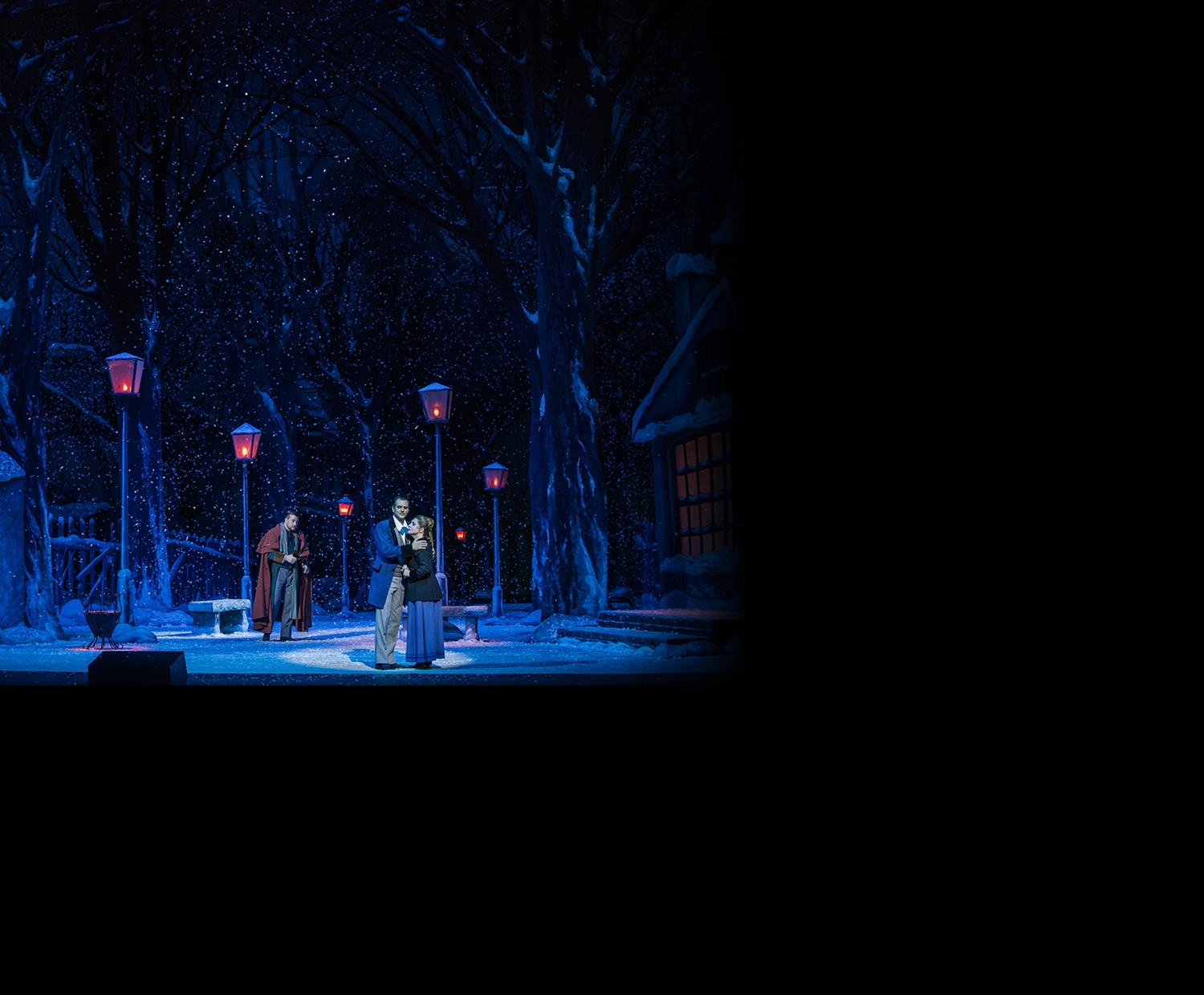

“It’s difficult to believe that Kálmán Nádasdy’s production, Gusztáv Oláh’s sets and Tivadar Márk’s costumes are now more than 75 years old. (…) After the curtain went up on the third act, one could see a toll gate shrouded in mist, with a foreshortened wintry path surrounded by gas lamps and trees receding into the backdrop. Snowflakes cascade down from the flies.”

Harald Lacina, Der neue Merker

Opera guide

Introduction

La bohème can be placed in multiple temporal contexts. First, there is the historical time of the story itself – around 1830 – then the calendar and seasonal time of the plot, which begins on Christmas Eve and is therefore predominantly set in winter, and of course, there is the chronological point of the opera’s creation in Puccini’s career. But there is also another, even more defining temporal dimension: La bohème takes place in the mythical time of youth. Realizing this can explain a lot, including the bohemians’ lifestyle and poverty. For their destitution is the result of a personal choice, not an inevitable fate of the artist, nor the consequence of social injustice. Behind it lies youthful recklessness and the desire for a life free from constraints – and in this sense, the resentment voiced by József Simándy in his memoirs about the character of Rodolfo is not entirely unjustified. After all, a responsible man would indeed rather gather some firewood in Act III than let his lover freeze beside him. But this character is neither a man burdened with responsibility nor a typical tenor hero: the story, ending with Mimi’s death, is in fact the final chapter of Rodolfo’s playful, self-dramatizing, and free-spirited youth.

“The music of La bohème was really written for immediate enjoyment... and in this judgment lies both praise and criticism.” This is how one of Turin’s newspapers dismissed Puccini’s new opera after its premiere, and this remark can paradoxically be seen both as a narrow-minded folly and as an insightful hit at the essence. In any case, this contemporary verdict clearly did no harm to La bohème, as the fact illustrates so eloquently that in the expression “ABC operas” – used in several languages to refer to the most popular repertoire pieces – the letter B stands for this opera. But really, why appeal to popularity when we so obviously have a deeply personal connection to it? We do not have to be bohemians or even young to feel the thrill of meeting someone new, the euphoria of coming together, the pain of parting, the grief of loss – or to hold our breath for the high C of “Che gelida manina.” Whether we find ourselves facing Gusztáv Oláh’s still powerfully effective, museum-like sets, unchanged since 1937, or Damiano Michieletto’s strikingly different, Parisian staging, which reached Budapest in 2016 – it makes no difference.

Ferenc László

B is for Bohème

“Dear Mr Director,

I would be most grateful if you could publish the following short notice in your newspaper. From Maestro Leoncavallo’s declaration in yesterday’s Il Secolo, the public must be convinced of my entirely honest intentions; for to be sure, if Maestro Leoncavallo, for whom I have long felt great friendship, had confided to me earlier what he suddenly made known to me the other evening, then I would certainly not have thought of Murger’s Bohème. Now – for reasons easy to understand – I am no longer inclined to be as courteous to him as I might like, either as a friend or a fellow musician. After all, what does this matter to Maestro Leoncavallo? Let him compose, and I will compose. The public will judge. Artistic precedent does not imply that identical subjects must be interpreted with identical artistic ideas. I only want to make it known that for about two months, namely since the first performance of Manon Lescaut in Turin, I have worked earnestly on my idea, and made no secret of this to anyone.”

This letter, written by Puccini and published in Corriere della Sera in March 1893, was the first news to the world of the arrangements for the opera which would become one of the most popular items in the repertoire for a long time to come, perhaps even for all time. The future staple middle member of the so-called ABC of operas (Aida, La bohème, and Carmen) was of course at the time still only a sketched draft: an ambitious plan of a composer who had only just tasted world fame, two librettists whose nerves were continuously challenged, and a music publisher who speculated cleverly but bravely. Anyhow, scarcely a few weeks after the sensational première of Manon Lescaut in Turin, Giacomo Puccini, his publisher Giulio Ricordi and the two writers Giuseppe Giacosa and Luigi Illica, were already discussing La bohème.

It is not known whose idea it originally was to choose the French “novel and play”, written some decades before, as the basis for the next Puccini opera. It is even more of a mystery how this piece of literature of a dualistic nature immediately became the theme of another opera in progress, composed by Leoncavallo. At any rate, the choice seemed obvious and risky at the same time. The French author Henri Murger (who generally spelled his first name with a ‘y’ in the English way) died young in 1861 at the age of 38. He published his series of stories Scènes de la vie de bohème between 1845 and 1849, later compiling them into a book and then rewriting them as a play for French audiences. The stories of penniless Parisian artists and their lovers were at once sentimental and ironic, elevated and frivolous, everyday and exotic, achieving outstanding success in their time. They have not been forgotten by posterity, either. Murger’s richly autobiographical work (or perhaps more properly, family of works) provided its bourgeois audience with a glimpse behind the scenes of the unusual and subversive lives of the bohemians, the milieu of free love with its emancipation of women, and, last but not least, the tear-inducing, lovelorn romantic world of the artist. With all the alluring and valuable qualities this world represented for Puccini and his collaborators, albeit with an added dose of sarcasm, it can also be said that several basic features of Murger’s work are actually not so far removed from his first international success, Manon Lescaut. Consequently, in addition to the predictable charges of immorality and excessive sensationalism, the work’s creators also took the risk that some might simply interpret the new opera as a thematic recasting of Manon Lescaut in another skin.

If Puccini and his collaborators, so often accused of convenience and even of laziness, had really been taking it easy, then they obviously would have chosen the theatrical version of the story as the base material of the new opera. But this is not what happened, as they all quickly recognised that the prose work preserves more of the originality of Murger’s vision and the human warmth of his humour and emotional feeling, in contrast to the forcedly lachrymose action of the play. Of course, there were elements of the play that nevertheless proved useful to adopt, primarily the sensible reduction in the number of characters and the merging of certain characters. For everything in Murger’s novel that would later comprise the second half of the first act of Puccini’s La bohème – in other words, the love-struck encounter of Mimì and Rodolfo – originally happens to a sculptor named Jacques and his terminally ill beloved Francine. Meanwhile, the closing scene that has moved the world’s opera audiences for more than 110 years – the death of Mimì – is a skilful condensation of everything Murger wrote about the deaths of Mimì, who is otherwise portrayed as somewhat soulless (but who even in the novel creates an impression with her pale little hands), and the aforementioned Francine.

The joint decision to proceed may thus have been taken at the beginning of 1893, although the path leading to the première on 1 February 1896 was neither easy nor direct, and certainly not devoid of frustrations for the writing partners. Puccini tested the two writers in all senses of the word, as he also tested Ricordi, the man who paved the way for his international success: testing their patience and forbearance, as much as their flexibility and congeniality. In the conventional sense, Puccini was not really what one would describe as an industrious artist, and of course it was not mere idleness that caused him to put his work on La bohème on hold from time to time. He needed, for example, to follow the progress of premières of Manon Lescaut in Italy and Europe, and he even visited Budapest in 1894, among other places, where he was immediately and hugely enthused at seeing and hearing the talents of the conductor Arthur Nikisch. However, besides Manon Lescaut’s conquest of the world, Puccini also found time for a whole host of other tasks during the years he worked on La bohème: he bought a yacht and founded a club for his friends, he was arrested for poaching, and on one occasion he was even taken for a spy at the sight of his modern camera apparatus. Moreover, Puccini also began to take interest in other themes while in the thick of preparations for the new opera. In 1894, his attention was captured by the setting to music of the story The She-Wolf (La Lupa) by Giovanni Verga, author of the literary classic Cavalleria rusticana. In 1895 – although it is true it caused no interruption to his work – he watched Sardou’s play La Tosca in Florence, with Sarah Bernhardt in the title role. (As an interesting aside, it is worth mentioning that neither the French drama nor the divine Sarah found favour with Puccini…)

What is more, Puccini had a huge number of misgivings in the course of collaborating on the work, which were an enormous strain on Illica, and even on the nerves of Giacosa, whose calm demeanour otherwise earned him the nickname of Buddha. This was partly because he was not unequivocally consistent with his earlier ideas, and partly because sometimes he was unable to express what he wanted in words: “something… something… something” – was how Giacosa caricatured the Maestro’s vacillation in a letter written to Ricordi. There was also a degree of fear behind this indecision and inconsistency, given that even in this period Puccini would sometimes express his own personal pessimistic view that “It is my fate to remain a local celebrity for my entire life.” And yet what was more pronounced was his feel for quality – not always fully expressed – and the knowledge, both learned and instinctive, of the mechanism of effects and audience reactions to musical drama which motivated Puccini’s objections and vetoes. In this way, for example, Puccini threw out from the libretto the entire act which would have been presented to the audience between the third and fourth acts as we see them today, in which Mimì leaves Rodolfo for her new paramour. It was also Puccini who had the protesting librettists cut back the episode of joyful, happy-go-lucky jesting and unbridled merriment of the four bohemians in the closing act, and with it the role of Schaunard, while the rousing close to the second act was added to the work at his discretion – albeit only in performances following the world première. And yet it is also a fact that Puccini could be convinced by an argument which took theatrical effect as its approach: it was in this way that the famous duet of Marcello and Rodolfo was eventually added to the beginning of the fourth act, becoming one of the biggest hits in the opera.

Even if in a protracted way and amid a small degree of ill feeling, La bohème was completed: in December 1895, the final flourish – or more precisely, a skull and two cross-bones – was added to the score with the death of Mimì. “Dear Puccini, if even now we have not succeeded in hitting the bullseye, then I’ll give up the profession and sell salami instead,” is how Ricordi enthused to the composer known in his private circle as the Doge, showing not only that he recognised it would be successful well in advance, but that he himself arranged its success in a professional manner. And yet the première in Turin conducted by Arturo Toscanini (on 1 February 1896) did not meet with resounding success among peers and critics. Some found the story too mawkishly sentimental, others objected to the upsetting naturalism of the poverty portrayed, while Turin’s leading daily newspaper summarised the première thus: “La bohème, just as it exercised no influence on the souls of the listeners, will leave no very great impression on the history of our operatic theatre; the author would do well to regard it as a momentary lapse and to happily amble along further on the path of art in future.”

The review of a rival local organ put it as follows: “The music of La bohème is really music made for instant enjoyment… and judging it in this way conceals both praise and criticism.” “Music made for instant enjoyment”, is a typical characteristic mentioned at every turn of La bohème, a work which became hugely popular among audiences from the very beginning and which conquered the world’s opera stages at lightning speed. (Not only did it chronologically precede Leoncavallo’s opera of the same name, but its success consigned the latter to long-lasting obscurity.) Of course, Puccini’s entire oeuvre was put under “suspicion” by contemporary critics, the most brutal attack appearing in Turin itself in 1912 in the shape of a 130-page pamphlet by Fausto Terrefranca, which analyses what makes Puccini sensationalist, purely commercial and devoid of imagination, and why he is in fact not a genuine musician. The dubious value of popular success and the suspect nature of direct emotional reactions also emerge in one of the first significant essays to appear in Hungarian writing on Puccini, published by Géza Csáth in the first volume of the periodical Nyugat. But this criticism is in vain, as opera audiences simply do not wish to “see reason,” and for a musician of the moment, the signs are that this given moment is one of everlasting value.

Ferenc László