Stephen the King

Details

In Brief

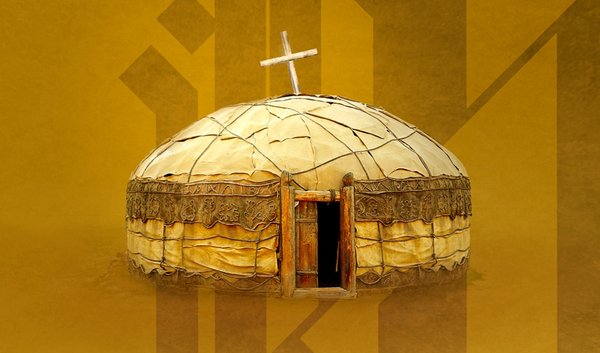

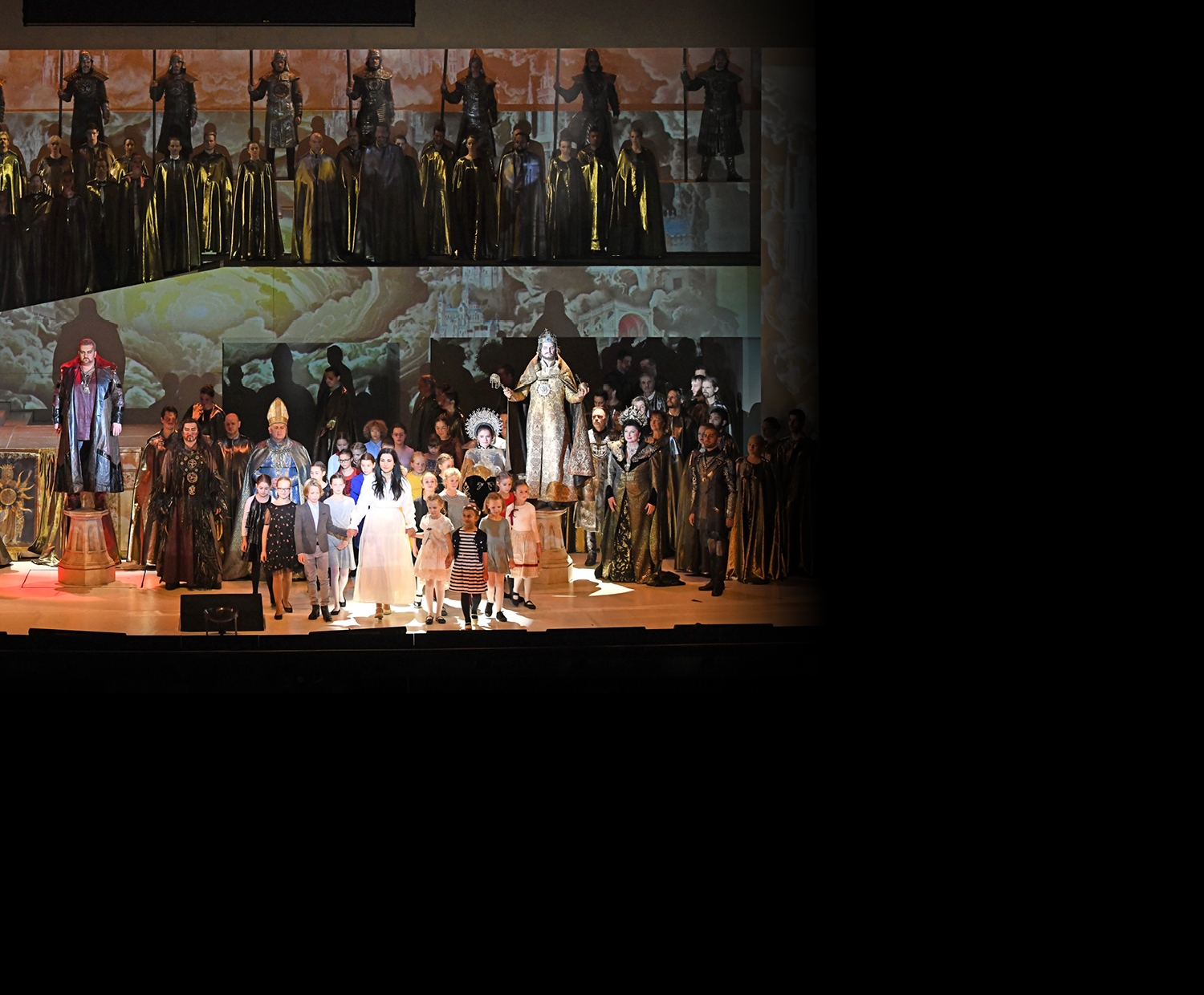

By far the most successful of the Hungarian crop of rock operas, ever since its original album release Stephen, the King has had not only symphonic features but has also been pervaded by the vocal, closed number structure characteristic of traditional operas, the presence of large tableaus, and instrumentation that gives the rock music universal perspectives. The poems for Levente Szörényi, who approached one of the fundamental stories in Hungarian history through Miklós Boldizsár’s play titled Ezredforduló (Turn of the Millennium), was written by his old co-author János Bródy. The Hungarian State Opera production staged the work with operatic instrumentation and opera singers in 2020. Thanks to the entirely symphonic score by composer Levente Gyöngyösi and the opera singers participating in the production, the work completely sheds the need for amplification, allowing new treasures to be discovered in the interpretation of Miklós Szinetár, the doyen of Hungarian directors. In this season, performances will start with the overture to Beethoven's König Stephan.

This production has been made possible through the mediation of the Zikkurat Stage Agency and Melody Kft.

Parental guidance

Events

Premiere: Oct. 22, 2020

Synopsis

István, the son of Grand Prince Géza, and the Bavarian princess Gizella are married. The people pray for the couple. In the festive atmosphere, the three Hungarian lords Bese, Solt, and Sur are already fantasising about their future successes. Réka, the Christian daughter of Duke Koppány, is praying, asking for the conversion of the pagans, when she is interrupted by one of her father’s pagan men, Laborc, who rejects the new God. After the death of Géza, Koppány and István have a falling out at the funeral: Koppány had been hoping, to no avail, that Géza’s death would absolve the former promise of István inheriting the throne.

The people ask for the peace of God, after which István and his mother Sarolt are entertained by folk musicians, which István finds to be overly old-fashioned. That’s when Laborc arrives at the scene. As a messenger from Koppány, he asks Sarolt to continue the ancient tradition of marrying him so they could rule together. Sarolt rejects the proposal and has Laborc executed. The three profit-seeking lords again show up, this time taking István’s side. However, he does not fall for their worthless flattery. After Sur, Solt, and Bese leave, István gives voice to his doubts, but Sarolt fills him with hope. Others are also dissatisfied: Gizella wants more from István as a husband, and the knight Vecellin wants more from him as a military leader. Asztrik, the head of the missionaries, appoints István Grand Prince.

Duke Koppány and his shaman Torda address Koppány’s followers. His admirers Boglárka, Enikő, and Picúr try to woo him, but the Duke resists. The three turncoat gentlemen arrive with the news that István has been appointed Grand Prince. They are now trying their luck by siding with Koppány, but he does not support them, either. Torda makes the most of the tension in the air, kindling the fire of the Duke’s belligerence and proceeding to make a sacrifice to the ancient gods. Réka tells her father about a nightmare she had, where she saw him quartered as a traitor. However, Koppány sees no solution than to take up the fight. István now arrives on scene and offers to hand over his power to Koppány on condition he turns to Rome, but Koppány does not accept the throne. Torda arrives with a bloody sword and a call to arms. In the battle, Koppány suffers a humiliating defeat.

Women, elders, and children mourn the victims of the battle, the fight between two siblings. The victorious army celebrates István when Réka arrives to ask for her father’s body so she may bury him. István would be happy to fulfil the girl’s request, but Sarolt opposes her, and issues her command: “Quarter his body!” Koppány’s body is cut in four, and the people praise István. The Abbot Asztrik crowns István in the name of God, using the crown provided by the pope.

Media

Reviews

"Everything on the stage of director Miklós Szinetár is presented with elemental force. That is partly due to the genre of the opera, the scenery, the large cast and everything that come out of the orchestra pit (...). Levente Gyöngyösi (...) created such a powerful arrangement for winds and strings, including harp, that the orchestration transforms every tune originally composed for broken chords, solo guitar and rocker voices coarse from cigarette smoke into ethereal music. And if there is something about the opera version of Stephen, the King that is clearly a plus compared to the original rock opera, it is the choir, performed by the Hungarian State Opera Chorus (directed by Gábor Csiki)."

F. Tóth Benedek, Index

Opera guide

Introduction

Hungary’s most popular rock opera is now living its umpteenth life, having in recent years left behind its status as an indispensable holiday staple and crossed over into the ranks of national classics that invite reinterpretation. And although ever since the open-air premiere in City Park – or at the very latest since the release of the double Hungaroton album (and of course the film) — we have truly come to feel that Szörényi Levente and Bródy János’s joint masterpiece belongs to us, there is still good reason to marvel at this latest stage of the work’s performance history. After all, it would be foolish to deny that for a long time it seemed as though Stephen, the King’s message (or its “message”) was too simple and straightforward for it to combine its popularity with the complexity of exciting ambiguity. This was the prevailing view despite the fact that the final, emphatically delivered spoken line of the piece – “With you, Lord, but without you” – has challenged those seeking to understand it right from the very beginning. Really, what does this statement mean?

Despite the assumptions above, the last few years’ various open-air and traditional theatre productions have visibly stirred and reshaped the aesthetic and interpretive context of Stephen, the King. Levente Gyöngyösi and the OPERA’s ambitious undertaking joined this trend too, presenting the audience with a version featuring symphonic orchestration and opera singers. Here, the reinterpretation primarily poses an apparently twofold but in reality single question to the work, and, of course, to us, the audience: can Stephen, the King bear, and can Stephen, the King that lives in our memories and souls bear this intervention? The success of the result depends at least as much on how strongly we cling to our old listening experiences as it does on whether the raw rock or folk-inspired musical idiom can break through the symphonic arrangement. This experiment is something both the audience and the performers must get used to and adapt to. When we hear the atmospherically powerful percussive accompaniment of “You’re So Far From Me”, Gyöngyösi’s version does indeed sound truly exciting. Elsewhere, we might be more inclined to question the chosen solutions. But then again, debates have never harmed the classics – nor contemporary experiments either.

Ferenc László

The director’s concept

At its world premiere 40 years ago, István, a király (Stephen, the King) was a revelation, a new voice, and it was met with resounding success. When I was asked to direct the piece after the many performances that have already been staged, this time as an opera, the question arose of how the operatic orchestration can offer something more and be different than the rock opera. While the rock opera has a certain monotonous suggestiveness that both demands and realises unity (guaranteed by both the uniform dance ensemble and chorus, which performed throughout almost the entire piece), the opera can be more colourful and eclectic, with the possibility of setting every single scene differently – at least, that is what I am aiming to accomplish.

This isn’t a historical piece, just like Don Carlo and Bánk bán aren’t either. There are a lot of details in it that may not be historically accurate. It is not likely that István’s mother Sarolt had influenced the events to such an extent, or that István had offered to hand over the throne to Koppány, or that Torda the shaman had mentioned the creation of the Danube Republic. Of course we can say that the shaman can see the future, but then he was wrong... Certainly, there are insinuations of certain things: pertaining not just to the present day, but also to past centuries. It is no mistake that the Hungarian national anthem, the Hymnus is played at the end of the piece, symbolising that this is what all of us as Hungarians are: we are Koppánys, Istváns, and we stand behind Koppány and behind István. Here we are, ten million of us, subjected to the geographic, historical, economic, and political situation. However, if there were a unity and cooperation, we would be able to forget who is an István and who a Koppány.

There used to be an approach of drawing a historical parallel between István and János Kádár, and making Koppány Imre Nagy, but this was spread mainly by persons who wanted to keep the piece safe. It does not have any such direct, commonplace meanings. However, it does have a political message, which is valid for all of the past centuries: the nation has often been divided, with two opinions meeting each other with varying levels of passion. However, this is true not only for the history of Hungary, but for all of humanity. Ancient Roman chariot races had the blue and the green parties, America has Republicans and Democrats, and Great Britain has people for and against Brexit. These issues are not divisions in current politics, but are differences in opinion that can be traced back hundreds of years, depending on social status, family backgrounds, and genetics, and they always define public life. So in that sense, it is current. Especially because Hungary has always been home to an István, who wants order and to belong to the West, but we have always also been a Koppány, who is a rebel, wants to change the world, and who is scared of the West, suffering from an inferiority complex. This duality, which can manifest even within the individual, dominates the piece, and this is what I would like to emphasise. It is important that both István and Koppány are right about certain things. It is not the good and the bad that are fighting against each other: both have good and bad in them. And there is also the large, quiet mass of people that acts as nothing but a passive onlooker, or may even be considered to be enduring the decisions made by others – they are the ones whom Réka personifies.

In addition to conflicts, problems, and historical motifs, Stepthen, the King even includes humour and irony, and I would not like the piece to be overly serious from its beginning to the very end, either. There is some irony in, for example, István, who is a realist politician and not a saint, just as Koppány is not evil, but is forced into a corner. Everyone is right in their own way. Bese, Solt, and Sur are able to adapt to everything, they are “journalists in every system”. That is the type of turncoats that they are, and that is what I call them in the piece. A society has all sorts of professions: executioners, prison guards. So why can’t we have turncoats as well? My aim is to create a many faceted performance.

Miklós Szinetár

Re-orchestrating a rock opera into an opera

This piece has garnered a lot of respect, and so I have not changed anything that would alter the original format. The new orchestration serves to create a musical world that meets the requirements of a type of operatic music while also retaining the intrinsic nature of the original music. We had to balance these criteria very delicately to realise these two goals. I wanted to show the operatic modus operandi that was present in the original work, and I wanted to use it to transform the entire piece in line with classical music requirements.

The starting point was that I shouldn’t use anything electronic for the piece. The drums, bass guitar, and electric guitars have been left out. Back in the day, Levente Szörényi personally played the guitar solo that accompanied Koppány and people on his side – it is now played by a distorted trumpet solo. Even though the guitar and the trumpet may seem to be quite different, they are not! The piece has a part that already uses classical music, which generally accompanies the parts of Bese, Solt, and Sur, as well as Sarolt. However, the parts that used rock music, for example the music that accompanies the parts of Koppány and Torda, replace the drums with acoustic percussion instruments – that pretty much goes without saying. The bass guitar can be replaced with a double bass. I also changed the rhythm, the rock groove that grabs the listener, but I kept its character. Besides these, I used an entirely average, romantic opera orchestra, similar to the type used by Verdi, with double woodwind instruments, an organ, and a harp. The organ is important for creating a religious atmosphere. It is a great help that many members of the Hungarian State Opera Orchestra are quite familiar with folk music, so I didn’t even have to re-orchestrate the folk music parts: all the musicians have to do is play those on violins and double basses in a more folksy manner. The vocal parts and melodies have been retained. The original was composed for rock music singers, who usually don’t have deep male voices. However, we wrote for opera singers, so the parts had to be transposed. As a result, Koppány’s solo has been shifted down and made baritone, and Réka’s has been shifted up. Gizella has been moved up by an entire octave.

It was a challenge to find a solution to changing a fifty-sixty year-old tradition in a manner that ensures it remains viable. I had to try out several types of rhythm combinations before I finally found the symphonic orchestra equal to rock grooves. In fact, it wasn’t the re-orchestration that was the most difficult. It is exciting to see that the piece has some special musical solutions that Szörényi had never used in his work before. For example, the “Quarter him!” part, which is widely known to be in five-four time, is quite modern, almost atonal. It is also interesting that the entirely different characters of styles form an organic unity. The long months I spent working on the piece showed me that István, a király (Stepthen, the King) has lost nothing of its freshness. It has been elevated almost to the level of Erkel’s Bánk bán.

Levente Gyöngyösi