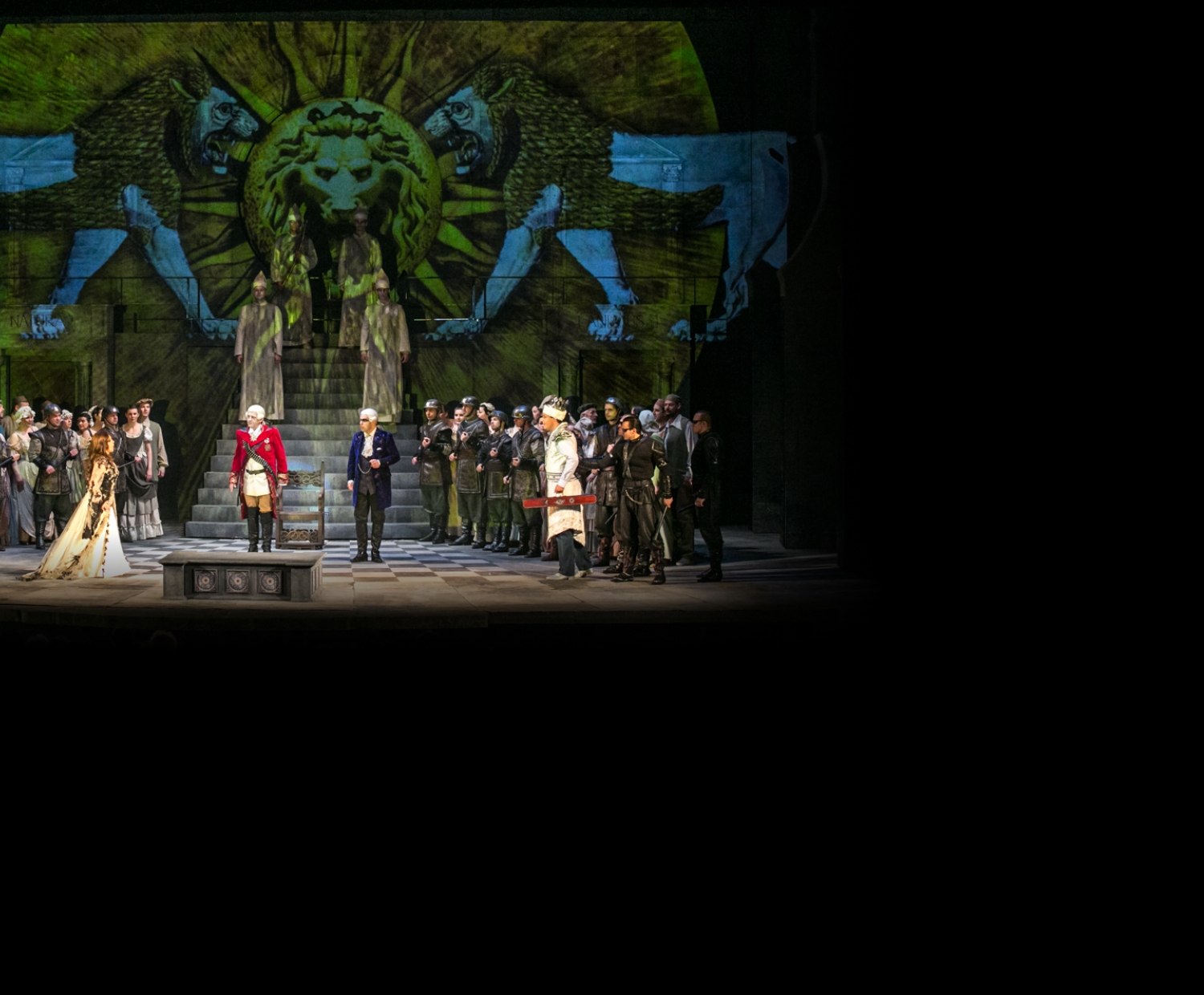

Die Zauberflöte (The Magic Flute)

Details

In Brief

The combination of Mozart's marvellous music and Schikaneder's coming-of-age storyline has something to tell us at every stage of life. No matter if you are discovering or rediscovering the work as a young lover, a parent, or with the wisdom of old age, this blend of the ethereal and riveting entertainment is always thrilling to watch. Miklós Szinetár's production is suffused with the opera's rich world of symbolism, with the sun always rising at the end.

Age restriction

Events

Premiere: April 12, 2014

Synopsis

Prologue

The Queen of the Night has lost all of her power. Following her husband's death, all of the land and property went to her and her daughter, Pamina, with the exception of one object: the disk of the sun, which the will entrusted to Sarastro. The Queen does not accept this, and has begun to fight for the return of the sun-disk.

Act I

Tamino is being pursued by a monster. The youth faints. Three ladies rush to his aid and slay the serpent. Each of the three place a spell on the handsome, but unconscious, young man. They must bring news of this development to their mistress, the Queen of the Night. However, all three want to be the one to stay behind to keep watch over the insensate young man. They argue, but then all end up leaving together.

Tamino awakes, and sees a strange human shape nearby. It is Papageno, the bird-catcher who receives wine and food from the ladies in exchange for his birds, and who also lives a merry life, with only one difficulty: he hasn't managed to find a wife. They start a conversation: Papageno pretends that he was the one who killed the monster. The returning three ladies hear him say this, and punish the boaster: from now on his birds will earn him only water to drink and stones to eat, and they also fasten a lock to his mouth. The ladies reveal that they were the ones who saved Tamino, to whom the Queen of the Night has sent a picture of her daughter, Pamina. Tamino falls instantly in love with the image. The girl, however, is the captive of a “wicked demon” named Sarastro, the ladies explain.

Accompanied by thunder and lightning, the Queen herself now arrives to inform Tamino that if he frees Pamina, the girl will be his. The Queen departs. The ladies remove the lock from Papageno's mouth and give Tamino a gift from their mistress: a flute whose bewitching music brings happiness to those who hear it. Papageno has had enough and is ready to move on, but the ladies stop him: at the Queen's command he must stand with Tamino and accompany him into Sarastro's realm. Papageno is quite upset to receive this news, and so in order to mollify him somewhat, the ladies give him a glockenspiel. Tamino and the bird-catcher will be guided on their way by three little boy-spirits.

Sarastro's palace: Papageno finds Pamina, who is at that moment attempting to escape. He tells her the whole story about how he and Tamino have come to rescue her. They set off in search of Tamino.

Meanwhile, the young man has requested that the three boys help him find his love. “Be steadfast, be patient... be a man,” comes the response. He's amazed at where the boys have taken him: instead of a formidable castle, he is confronted with a magnificent temple. Three times, he forcefully demands to be admitted. Only on the third attempt is he successful: an old priest asks him: “What do you seek in this holy place?” Tamino answers that he seeks “Love and Virtue”. The priest sees that Tamino is in fact being manipulated by the Queen of the Night and her thirst for vengeance. He explains that Sarastro is not a wicked sorcerer and that the Queen of the Night is no pitiable bereft mother. “O endless night!” Tamino laments, “When will you vanish? When shall my eyes see light?” The priest reveals to him only that Pamina is alive. Tamino begins to play the flute in the hope that its sound will bring forth his love. Even the animals of the forest venture forth at the sound of the wondrous music, but the girl does not appear.

At the same time, Pamino and Papageno are searching for Tamino, but instead are discovered by Monostatos, Sarastro's repulsive servant, who is hopelessly in love with Pamina. Papageno begins to play on his glockenspiel, hypnotising Monostatos and his entranced slaves into sedately listening to the music and then, completely enchanted, returning to their business. At this point, Sarastro enters with his attendants. Pamina admits to Sarastro that she had indeed attempted to escape, as Monostatos had been plaguing her with his undesired attentions. Sarastro is not angry with her, but he will not permit the girl to return to her mother, either, as that would cost Pamina her happiness. Sarastro professes that the Queen of the Night has overstepped her bounds. Monostatos leads in Tamino, who has been taken prisoner. The smitten couple behold each other for the first time. The servant expects a reward for his cunning, and is given one: twenty-seven lashes on the soles of his feet... At Sarastro's command, Tamino and Papageno are led to the Temple of Ordeals, where their souls will be purified.

Act II

Sarastro and his priests assemble for a ceremony. Tamino has agreed to undertake the three trials in order for the veil of night be lifted from his eyes, thus making him an Initiate. The priests decide that they will support the youth. They pray for the gods Isis and Osiris to provide wisdom and patience to the future couple, and even if they fail at the trials, for the gods to still accept them.

Two priests prepare the two young people for the first test. Tamino has resolved to submit himself to anything, even at the price of death. Papageno is no longer quite so dedicated: all he wants to do is eat, drink, and maybe have a little wife. But if he can only have the latter by undergoing a trial, then he would prefer to remain single. The priests, however, inform him that there exists in the world a certain young and pretty Papagena...

The first trial begins: they may not speak with women at all.

The two men are in total darkness. The three ladies steal in and inform them with resignation that Tamino's fate is sealed: they are going to lose. They say that “whoever joins the order, goes straight to hell!” Tamino wisely remains silent, but Papageno is so terrified that he cannot keep his mouth shut. Finally, the voices of the initiates are heard, accompanied by thunderclaps, whereupon the ladies race off in fear. The two priests congratulate Tamino: he has passed the first trial.

Monostatos creeps up on the peacefully sleeping Pamini. He too would like a mate, but love eludes him, as everyone is terrified by his external appearance. He asks the Moon to turn away while he steals a kiss, and at that moment the Queen of the Night appears. When she learns from Pamina that Tamina has switched sides and joined Sarastro, she falls into a monstrous rage. Before storming off, she gives her daughter a dagger and a threat: if she does not kill Sarastro, she will be disowned. Monostatos, who has watched the entire scene in hiding, offers the girl a deal: he will help her in exchange for her love. Pamina rejects him, whereupon the embittered Monostatos attempts to stab her. Sarastro intervenes: Monostatos is packed off and hurries off to the Queen of the Night. Pamina pleads with the high priest not to punish her mother. Sarastro reassures the girl that there is no place for revenge inside the walls of the temple.

The two priests lead Tamino and Papageno to the second trial. They must continue to keep silent. An ugly old crone appears and speaks with Papageno. She tells him she has a lover, who is ten years older than her and whose name is... Papageno. Thunderclaps remind the bird-catcher that it would best for him not to respond...

The three boys appear. They have brought the flute and the glockenspiel that had been taken away from them. Sarastro has asked that they be returned to their owners. A table full of food and drink appears. Papageno happily tucks in, but Tamino prefers to play his instrument. At the sound of the music, Pamina finds them. Her lover, observing the rules of the trial, voicelessly draws away from her. The girl thinks that Tamino no longer loves her. Broken-hearted, she departs.

The chorus of priests prays for Tamino.

Papageno has failed the tests. He attempts to find Tamino and the exit. The priests inform him that the gods will excuse him from the punishment that he deserves. But on the other hand, he may not partake in the privileges of the Initiates. The bird-catcher informs them that all he wishes for is a little wine, which he receives. And then suddenly he is overcome by a deep emotional longing: he wants a mate! The old crone he had met earlier dances in and tells him that either he must settle for her, or he will never again see sunlight or good food, not to mention a wife. The terrified Papageno swears to always be faithful to her, at which point the old woman turns into the young and beautiful Papagena. The astonished Papageno, however, is not yet worthy of his mate, and so the priest leads the girl away.

The three boys greet the rising sun. Pamina approaches, overcome with grief that Tamino had been capable of abandoning her. She takes out the dagger that her mother had given her, and raises it to plunge into herself. The three boys put a stop to this, telling her that Tamino really does love her. Everyone goes off to find the young man.

Tamino is in the chamber of fire and water. He would rather die than give up on his mission. Pamina appears, and together, hand in hand, they continue on their path. They stop before the gate of terror, behind which death lurks. At Pamina's wise suggestion, they make use of the flute's power to aid them, and succeed in crossing the fire. They have sanctifies their bond to Isis and may enter the temple.

Meanwhile, Papageno is searching madly for Papagena. Ever since meeting his betrothed, he has been desperate to find her again. He tries to call her on his pipes, but it is no use. Crestfallen, he attempts to hang himself, but the three boys intervene yet again, counselling him to play the glockenspiel instead. The music's power proves triumphant once more: out comes Papagena, and at last their life together stands wide open before them, as they plan to make many little Papagenas and Papagenos.

Monostatos slinks back to the Queen of the Night and her three ladies. The Queen promises him Pamina's hand in marriage in exchange for his services. While planning an assault against the Brotherhood, they suddenly collapse to the ground, their power broken: the sun has risen and all is illuminated. Sarastro and his attendants enter. “The rays of the sun banish away the night; Fortitude is victorious, and thus Beauty and Wisdom win their eternal reward.”

Media

Reviews

“The new production of Die Zauberflöte at the Erkel Theatre thus has many things of value to discover in terms of the musical implementation.”

Péter Zoltán, Operaportál

Opera guide

Introduction

Compared to the fact that The Magic Flute has enjoyed unbroken popularity almost from the very beginning and remains consistently among the most frequently performed operas, it is surprisingly full of problems. You could already read above about the attempts to interpret and decipher the work, so here let me just state the three main fundamental contradictions that dominate its performance and reception history. Namely, that Mozart and Schikaneder’s joint creation is almost always simultaneously condemned for the libretto’s naive silliness, praised (and endlessly analysed) for its layered and enigmatic symbolism, and treated as the obligatory first stop for children visiting the opera. The fact that this extremely complex situation has existed undisturbed for as long as anyone can remember is not just an intriguing curiosity, but in fact a highly revealing and distinctive example of how opera performance and opera culture work. This kind of contradiction simply wouldn’t be conceivable in any other branch of art: in literature, for instance, it might take James Joyce, a hopelessly trashy pulp novel, and The Little Rooster and the Turkish Sultan to jointly cover The Magic Flute’s function in the world of opera. The carefree sensual immersion, the simultaneous disapproving yet indulgent head-shaking, the almost compulsive puzzle-solving, and the childlike sense of wonder all coexist eternally – this is how we consume The Magic Flute, and this is what we get used to from the very beginning in the opera house. And it is by no means entirely impossible that, in the end, the explanation is simply what the punchline from Love and Death, Woody Allen’s film – shot partly in our very own Opera House – suggests about The Magic Flute: “– Oh, there’s something about this Mozart!” “– Maybe it’s the music that enchanted you so much.”

Ferenc László

Musical adventure

“This image is of such enchanting beauty, / As no eye has ever seen before. / I feel, heavenly vision, that through you / My heart begins to stir anew” – this is how Mihály Csokonai Vitéz translates Tamino’s magical Portrait Aria. The first version bore the title The Witch’s Pipe, while another fragment of a translation used The Magic Pipe. Despite this early reception, neither title took root, and the first Hungarian-language performance (in Košice in 1831) was given under the title The Fairy Pipe. The Magic Flute is the initiation rite and love struggle of two pairs of lovers, who undergo (or fail to undergo) various trials full of allegorical meaning. Stefan Kunze considered the opera a triple hybrid: a clever combination of folk theater based on fairy tale, Enlightenment didactic drama, and an initiation ritual burdened with the heavy symbolism of Freemasonry (Rosicrucianism). Some pushed this even further into political allegory: in this reading, the Queen of the Night represents Maria Theresa, Monostatos embodies the Church, Sarastro himself is Ignaz von Born – the well-known Freemason scholar of the era – while the hierarchical layers represent various dimensions of existence, from corporeality to spiritual heights.

Jan Assmann devoted an entire book to interpreting the opera as a mystery play: he considers the work a mythopoetic manifestation of “spiritual alchemy,” a modern allegory of the mysteries of Isis, with the plot itself presenting the structure of a ritual. But far more important than all these ingenious symbolic analyses is the music’s breathtaking adventure: how it conquers depths and heights at once, how it gives voice to the human as an instinctive, animate being and to a nearly unattainable, yet so perceptibly intuited, transcendent truth. Spike Hughes also pointed out that this Mozart work does not necessarily follow naturally from his previous ones; its eclectic perspective and musical mind-mapping may at first confuse or even disappoint Mozart devotees. Yet this disappointment quickly dissolves in the ontological serenity that thoroughly pervades this worldview – indeed, this world-construction. It can be seen and heard by child, adult, or elder: it has something meaningful to say to every generation. Its layered nature guarantees the magical ability to always speak differently: in this sense too, it is an enchanting “Magic Pipe.” The eternal labyrinth adventure of self-knowledge, the more or less successful “gold-making” of creating ourselves – and we have not even mentioned love yet, which is the guiding thread of all discovery.

Zoltán Csehy

Differences and balance

Both in its text and its music, the piece is interwoven with the semiotic system of Masonic rites and symbols, for example the magic number three, the use of inverted triangles and pyramids, as well as the motif evoking the three knocks in reference to the ritual of the Viennese lodge. In connection with this, there is a school of thought that the figure of The Queen of the Night was actually a subtle parody of Empress Maria Theresa, the Habsburg ruler who exhibited profound antipathy for the Brotherhood of Freemasons. Looked at in this light, different interpretations can be found for lines like “Man and Wife, Wife and Man reach up and attain divinity”. This passage is especially delectable if we remember that it is sung as a duet by a princess (Pamina) and an “everyman” (Papageno) driven by similar emotions, thus breaching every rule of social hierarchy. This is just one example showing how infinitely rich the opera’s plot is and how universal its symbolism is. We can see in it a “divine comedy” with mystical and supernatural dimensions in which the main characters start out in a state of catastrophe and eventually find harmony.

The central focus of the opera is the process of becoming an adult, as we watch the character development of Pamina and Tamino. At the beginning of the piece, Tamino is a goofy adolescent. Lacking both an adequate weapon and presence of mind, he faints and is eventually saved by three women. Later on, he believes himself to be in love for the first time in his life – with a portrait. Then a mother figure appears before him: so impressed is he with the Queen of the Night that he instantly obeys her without question. The same is true for Pamina. Initially also unable to face her own fears, she faints helplessly when Monostatos offends her and is dependent on her mother; this is why Sarastro keeps her captive: if she went back to her mother, she would remain a child forever and never learn how to fight her demons.

The Queen of the Night represents the dark side of the Mother. She keeps everybody she can under her spell. She has built up a masculine world for herself with ladies-in-waiting who behave in a masculine manner. Unable to accept a superior world order, she has no problem giving up her own daughter in order to reach her aims, in part by immediately offering her to the first (and then the second) passer-by, and then when she wants to use Pamina for her own interests, she threatens to disown her daughter unless she fulfils her wish. She thinks in a blind and irrational way and acts in haste. In this, she is the perfect opposite of Sarastro, the embodiment of the father figure. This spirit is perfectly evident in the music. One need only compare the Queen of the Night’s exalted and vengeful arias rising to increasing heights with

Sarastro’s sober utterances. The High Priest teaches both Tamino and Pamina to behave like men.

This is the point in the piece when feminists begin to shriek. However, Mozart and his librettist were merely weaving into the work the psychological fact, now an obvious one, that men and women are constructed from a mixture of so-called “masculine” and “feminine” characteristics. Neither can exist without the other. Tamino, a child with feminine traits, must grow into a prudent and resolute man. And Pamina herself must armour herself with masculine characteristics too so as to develop fully in her femininity and become a worthy partner to Tamino. (She succeeds in rising to the occasion: she is the one who helps Tamino through the fire and water in his last trial.) They have to become aware of and understand each other’s real intentions as well as their own goals and feelings so that they can find their way in the world. Only the “divine law” leads to the right road: a pure heart, a noble aim, sober and calm way of thinking, unselfishness, persistence and patience. Tamino and Pamina fall in love with love. It is only after these trials and tribulations, when they are both cognizant of themselves and their hearts, that they arrive at the beginning of their common road, on which they can at last set off together, hand in hand.

Papageno only manages to get close to this divine secret. He is a kind but fallible figure, and happiness to him means having a full belly and being left in peace. Nevertheless, he also reaches a dramatic point in the story: after finding and losing his Papagena, he loses his old good cheer and no longer sees the point of being alive. So, he develops too in the course of the opera: he finds something without which his life seems meaningless. At the end of the piece, the “feminine” and the “masculine” become balanced, Pamina and Tamino sing in harmony, and female voices join Sarastro’s “male choir”. The darkness of night is replaced by the sun and enlightenment.

Judit Kenesey